Ever stopped to think about how often you use the phrase “to be” in everyday conversation? It’s arguably the most fundamental verb in the English language, yet its simplicity masks incredible complexity. From basic grammar to profound philosophical questions, “to be” shapes how we express existence, identity, and states of being. In this comprehensive guide, we’ll explore the many dimensions of this essential verb—examining its grammatical functions, philosophical implications, and practical applications across contexts.

Whether you’re a language learner struggling with its irregular forms, a writer seeking more precise expression, or simply curious about the deeper meanings behind this common verb, this article will deepen your understanding of what it truly means “to be.”

Introduction and Basic Definitions

The Essential Guide to Understanding “To Be”

You’ve likely used it thousands of times today already—the verb “to be” isn’t just common; it’s absolutely essential to English communication. In fact, it’s impossible to speak or write without encountering forms like “am,” “is,” “are,” “was,” “were,” “been,” or “being.”

What makes this tiny verb so powerful? Well, it’s the linguistic glue that binds our sentences together! As both a main verb and an auxiliary helper, “to be” performs multiple grammatical functions that can’t be replaced by any other word. It expresses existence (“I am”), describes states (“She is happy”), forms passive voice (“It was built”), and creates progressive tenses (“They are walking”).

Beyond grammar, though, “to be” carries philosophical weight that few other words can claim. From Shakespeare’s famous soliloquy to existentialist philosophy, this verb raises profound questions about existence itself. As we journey through this article, we’ll unpack both its practical applications and deeper implications.

What Does “To Be” Mean?

At its core, “to be” expresses existence or state. It’s what linguists call a copula—a linking verb that connects subjects with their predicates. When you say, “I am tired,” you’re using “to be” to link yourself (the subject) with a condition (the predicate).

But here’s the fascinating thing—no other verb in English serves as many functions! Consider these varied uses:

- Expressing existence: “There are many stars in the sky.”

- Describing identity: “She is a doctor.”

- Indicating location: “We are at the store.”

- Forming continuous tenses: “He is working late.”

- Creating passive constructions: “The cake was eaten.”

The irregularity of “to be” reflects its ancient origins and essential nature. Unlike most verbs that follow predictable patterns, “to be” pulls from different linguistic roots—which is why “am,” “is,” and “are” look nothing alike! This irregularity isn’t just a quirk; it’s evidence of how fundamental this concept is across human languages.

What’s particularly interesting is how “to be” functions as both a complete thought and a grammatical helper. When someone asks, “Who’s there?” and you answer, “It’s me,” you’re using “to be” as a complete statement. But when you say, “I’m working,” it’s helping to form the continuous tense. This versatility makes it simultaneously the simplest yet most complex verb in English.

No wonder it’s estimated that forms of “to be” account for approximately 8% of all words in typical English text! From casual conversation to formal writing, academic discourse to poetic expression, “to be” isn’t just a word—it’s the verbal foundation upon which we build meaning.

As we dive deeper into its grammatical functions in the next section, you’ll gain a clearer understanding of how mastering this versatile verb can transform your entire approach to language.

Grammatical Usage

The Grammatical Functions of “To Be”

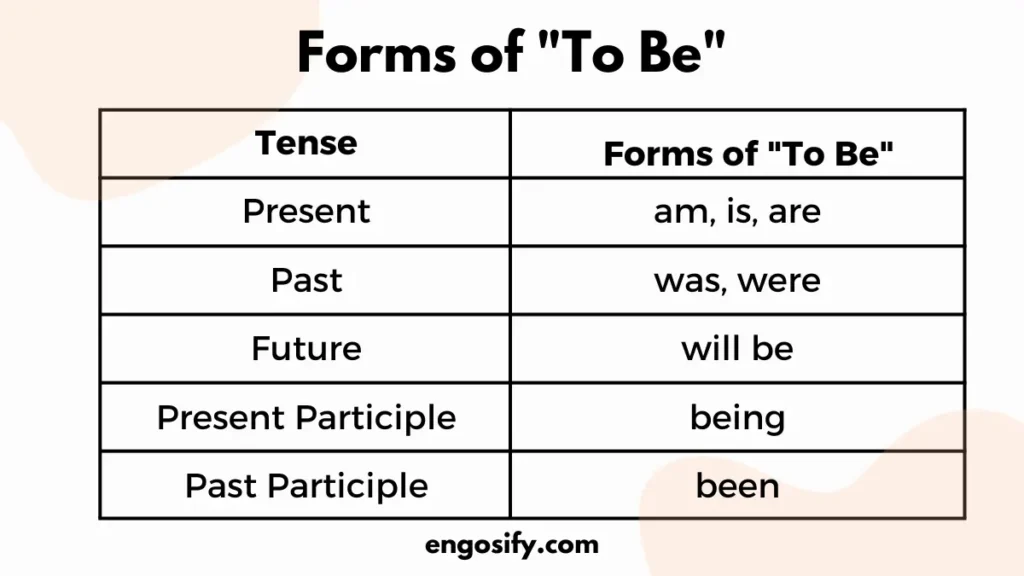

Let’s dive into the nitty-gritty of how “to be” actually works in everyday language. This chameleon-like verb takes on different forms depending on person, number, and tense—which is why we end up with “am,” “is,” “are,” “was,” “were,” “been,” and “being.” Unlike regular verbs that simply add “-ed” or “-ing,” “to be” transforms completely!

The present tense forms include:

- I am (first person singular)

- You are (second person singular)

- He/she/it is (third person singular)

- We are (first person plural)

- You are (second person plural)

- They are (third person plural)

While the past tense simplifies to just two forms:

- I/he/she/it was (singular)

- You/we/they were (plural)

What’s truly remarkable is just how frequently we use these forms. Linguistic research shows that “to be” appears more than twice as often as the next most common verb in English! It’s no exaggeration to say that roughly 3-4% of all words spoken or written in everyday English are some form of “to be”. That’s stunning when you think about it—nearly 1 in every 25 words!

As an auxiliary verb, “to be” helps form progressive tenses (“I am writing“), passive voice (“The book was written”), and even perfect progressive constructions (“She has been working”). It’s like the Swiss Army knife of verbs—endlessly adaptable to different grammatical needs.

“The beauty of ‘to be’ lies in its versatility,” notes Dr. James Miller in his comprehensive guide to English verb tenses. “No other verb carries such grammatical weight while remaining invisible to most speakers.”

“To Be” as a Linking Verb

As a linking verb, “to be” creates a bridge between subjects and their descriptions or identities. This isn’t about action—it’s about equivalence or state.

Consider these examples:

- “The sky is blue.” (linking subject to a quality)

- “My brother is a teacher.” (linking subject to identity)

- “The meeting was yesterday.” (linking subject to time)

In each case, “to be” doesn’t describe an action but rather establishes a relationship. It’s saying, essentially, “these things equal each other” or “this subject exists in this state.”

What makes this function tricky for many English learners is that the verb itself carries almost no concrete meaning. It’s a conceptual connector—an equals sign made verbal. That’s why translating “to be” constructions into other languages can be challenging. Many languages use different verbs for different states of being, while English relies heavily on this single, all-purpose verb.

The linking function also explains why “to be” so often partners with adjectives. When you say “I’m exhausted,” you’re using “to be” to connect yourself to a temporary state. Compare this with Spanish, which might use “estar” for temporary conditions versus “ser” for permanent characteristics—a distinction English doesn’t make grammatically.

“To Be” in Passive Voice Constructions

One of the most powerful—and sometimes controversial—uses of “to be” is in forming passive voice. Here, “to be” combines with a past participle to shift focus from the doer to the receiver of an action.

Active: “The committee approved the proposal.” Passive: “The proposal was approved (by the committee).”

The passive construction uses “to be” plus the past participle (“approved”) to emphasize what happened rather than who did it. This can be incredibly useful when:

- The doer is unknown: “My car was stolen.”

- The doer is irrelevant: “Mistakes were made.”

- You want to emphasize the receiver: “The cure was finally discovered.”

However, passive voice has gotten a bad rap! Many writing guides discourage its use, claiming it creates wordiness and vagueness. While overuse can indeed lead to flabby prose, strategic deployment of passive constructions adds valuable flexibility to your writing toolkit.

The key is intention. Are you using passive voice to obscure responsibility (“Rules were broken”) or to maintain proper emphasis (“The Mona Lisa was painted in the early 16th century”)? The difference matters tremendously.

When used thoughtfully, passive constructions with “to be” allow for sophisticated sentence structures that maintain thematic coherence. They help you control what information comes first in your sentences, guiding your reader’s attention precisely where you want it to go.

Advanced Grammar Applications

Complex Uses of “To Be” in English

You’ve mastered the basics, but “to be” gets truly fascinating when we examine its advanced applications. The progressive tenses—those continuous forms that express ongoing actions—rely entirely on forms of “to be” paired with present participles.

Let’s break this down:

- Present progressive: “I am working” (current, ongoing action)

- Past progressive: “They were dancing” (ongoing action in the past)

- Future progressive: “We will be traveling” (ongoing action in the future)

- Present perfect progressive: “She has been studying” (ongoing action from past to present)

- Past perfect progressive: “I had been waiting” (ongoing action before another past event)

What’s happening here is quite remarkable. The “to be” verb handles the grammatical heavy lifting—carrying person, number, and tense information—while the “-ing” form delivers the action’s content. It’s like “to be” provides the grammatical framework that allows the main verb to express continuous action.

The perfect progressive forms are particularly intricate. In a sentence like “She has been working since morning,” we’re using three verbs: the auxiliary “has,” the “to be” form “been,” and the main verb “working.” This construction communicates not just that an action happened, but that it started at a specific point and continues through time—all thanks to the versatility of “to be.”

Conditional structures also lean heavily on “to be.” Consider:

- “If I were you…” (hypothetical present)

- “She would be finishing now if…” (hypothetical continuous)

- “I would have been promoted if…” (hypothetical perfect)

Notice how “were” appears in hypotheticals regardless of person (“If I were” rather than “If I was”), preserving one of the few remaining subjunctive forms in modern English.

“The complexity of ‘to be’ in English reflects deeper patterns of how we conceptualize existence and action through time,” explains Dr. Elena Rodriguez in her work on philosophical concepts of being and existence. “Few other languages place so much grammatical weight on a single verb.”

Idiomatic Expressions Using “To Be”

Beyond grammar rules lie the colorful idiomatic expressions built around “to be.” These phrases often cannot be literally translated and must be learned as complete units:

- “To be or not to be” (Shakespeare’s famous contemplation of existence)

- “It is what it is” (acceptance of an unchangeable situation)

- “I’m all ears” (ready to listen attentively)

- “She’s been through the wringer” (experienced difficulties)

- “They’re on the fence” (undecided)

- “We’re in the same boat” (sharing a difficulty)

- “You’re toast!” (in trouble/defeated)

What’s fascinating is how these expressions evolve. “Been there, done that” emerged in the 1980s and rapidly became ubiquitous, while “I’m good” as a refusal gained popularity in the early 2000s. These expressions show how “to be” serves as a foundation for linguistic innovation.

Regional variations abound too. In Southern American English, you might hear “I might could be interested,” combining multiple auxiliaries in a way standard English doesn’t allow. In Scottish English, “I’m away to the shops” uses “to be” where standard English would use “go.”

The historical development of these idioms reveals cultural attitudes toward existence and state. The very British “I can’t be bothered” expresses a specific type of unwillingness that has no exact equivalent in American English. Meanwhile, the increasingly common “I’m like” as a quotative (“I’m like, ‘No way!'”) shows how “to be” continues to expand its functions in contemporary speech.

What makes these expressions so powerful is their economy—they pack complex meanings into simple structures, all pivoting around forms of “to be.” By mastering these idioms, language learners move beyond mechanical correctness toward the natural fluency that characterizes native speech.

Philosophical Dimensions

The Philosophy of Being and Existence

Beyond grammar rules and everyday usage, “to be” opens the door to profound philosophical questions. What does it mean to be? This seemingly simple question has occupied the greatest minds throughout history, from Aristotle and Plato to Heidegger and Sartre.

The concept of “being” versus “becoming” divided ancient Greek philosophers. While Parmenides argued that true reality is unchanging and singular (pure being), Heraclitus countered that everything exists in constant flux (becoming). This tension—between permanent existence and continuous change—still resonates in how we use “to be” today.

When you say, “I am tired,” are you expressing a temporary state or something essential about yourself? The grammar doesn’t distinguish, but philosophers have long debated this distinction. In fact, the very structure of “to be” statements influences how we perceive reality. Consider:

- “She is beautiful” (implies an inherent quality)

- “The earth is round” (expresses a seemingly permanent truth)

- “I am a teacher” (suggests identity)

Each statement makes an ontological claim—an assertion about the nature of being—using the same simple verb structure.

Existentialist philosophers like Jean-Paul Sartre famously distinguished between “being-in-itself” (unconscious existence, like rocks or tables) and “being-for-itself” (conscious existence, like humans). For Sartre, human consciousness is characterized by nothingness—we exist in the space between what we are and what we’re not yet. His famous line, “existence precedes essence,” challenges the idea that we have fixed natures, arguing instead that we create ourselves through choices.

“The verb ‘to be’ doesn’t just describe existence—it shapes how we conceptualize it,” writes philosopher Martin Heidegger in his analysis of philosophical concepts of being and existence. “Different languages structure the concept of being differently, revealing distinct cultural understandings of reality.”

This isn’t just abstract theory—it affects everyday thinking. E-Prime, an experimental English variant that eliminates all forms of “to be,” forces speakers to rethink statements like “This is good” as “I enjoy this” or “Many people value this.” Proponents argue this promotes clearer thinking by distinguishing observations from judgments.

“To Be” in Literature and Poetry

Literature has long explored the existential implications of “to be,” with Shakespeare’s “To be or not to be” standing as perhaps the most famous meditation on existence in Western literature. This soliloquy from Hamlet weighs the very value of continued existence against non-being, using “to be” both literally and metaphorically.

Poets regularly exploit the ambiguity of “to be” to create layers of meaning:

- “I am nobody! Who are you?” (Emily Dickinson playing with identity)

- “To see a World in a Grain of Sand… And Eternity in an hour” (William Blake connecting microcosm and macrocosm)

- “I am large, I contain multitudes” (Walt Whitman challenging singular identity)

What makes “to be” so powerful in literature is its capacity to bridge concrete and abstract meanings. When Robert Frost writes, “The road not taken was grassy and wanted wear,” he’s using “was” to describe both physical attributes and metaphorical significance.

Literary devices often pivot around forms of being. Personification—”The wind was angry that night”—uses “to be” to attribute human qualities to non-human entities. Metaphor—”Time is a thief”—uses it to create equivalence between unlike things.

T.S. Eliot’s opening to “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock” demonstrates how “to be” can create atmosphere: “Let us go then, you and I, / When the evening is spread out against the sky / Like a patient etherized upon a table.” Here, “is spread” creates both visual imagery and emotional tone, showing how this versatile verb works simultaneously on multiple levels.

“Literary masters intuitively understand what linguists formally study—that ‘to be’ functions as both the simplest and most complex verbal concept,” notes literary critic James Wood. “Its apparent simplicity makes it the perfect vehicle for profound questions.”

Learning and Teaching “To Be”

Common Challenges When Learning “To Be”

If you’ve ever taught English to non-native speakers, you’ve witnessed the struggle with “to be.” What seems intuitive to native speakers can become a grammatical minefield for learners. Why is this fundamental verb so challenging?

First, there’s the irregularity. Most verbs follow predictable patterns—add “-ed” for past tense, “-ing” for continuous forms. But “to be” throws this predictability out the window! The jumble of “am,” “is,” “are,” “was,” “were,” “been,” and “being” follows no obvious pattern, requiring pure memorization.

Then there’s the matter of language transfer. Many languages structure existence differently:

- Some languages (like Russian in present tense) often omit the equivalent of “to be” entirely

- Others (like Spanish with “ser” and “estar”) use different verbs for permanent versus temporary states

- Still others attach “to be” meanings to pronouns or other words

A Chinese speaker might say “I happy” because Mandarin doesn’t require a linking verb in such constructions. An Arabic speaker might struggle with “is” versus “are” because Arabic uses a different syntactic approach to agreement.

Subject-verb agreement creates another hurdle. The sentence “There ___ five books on the shelf” trips up countless learners. Is it “is” (agreeing with “there”) or “are” (agreeing with “books”)? Even advanced learners hesitate here.

“The acquisition of ‘to be’ functions follows a predictable sequence,” explains language researcher Dr. Maria Chen in her resources for mastering English verb forms. “Learners typically master the present forms before past, simple before progressive, and main verb functions before auxiliary uses.”

Interestingly, research shows that immersion students often learn irregular forms like “to be” faster than those studying through formal grammar instruction alone. The frequency of these forms in natural speech creates countless opportunities for absorption—proving sometimes that more exposure trumps more rules.

Advanced Mastery of “To Be”

True mastery of “to be” goes beyond mechanical correctness to include subtle distinctions that even advanced learners often miss. Consider these nuances:

The subjunctive mood preserves distinctions many native speakers have abandoned:

- “If I was there…” (indicative, suggesting it might have been true)

- “If I were there…” (subjunctive, purely hypothetical)

The contracted forms carry distinct registers:

- “I am not going” (formal, emphatic)

- “I’m not going” (neutral)

- “I ain’t going” (informal, dialectal)

Even word stress creates meaningful differences:

- “She IS coming” (emphasizing certainty)

- “She is COMING” (emphasizing the action)

Advanced learners must also navigate subtle distinctions in formality. Compare:

- “It is I” (traditionally correct but extremely formal)

- “It’s me” (standard in contemporary usage)

- “That’s her” (informal but universally accepted)

The omission of “to be” in certain contexts also requires advanced understanding. Headlines often drop it (“President Elected”), as do certain reduced clauses (“The work [that was] completed yesterday…”).

What separates advanced from intermediate users is the ability to deploy these distinctions intentionally rather than accidentally. An advanced speaker knows when “It is what it is” communicates resignation better than “That’s how things are,” understands why “I’ve been to Paris” differs from “I went to Paris,” and recognizes when “That would be inappropriate” delivers a softer refusal than “That’s inappropriate.”

As with many aspects of language mastery, developing an intuitive feel for “to be” ultimately matters more than memorizing rules. Through extensive exposure to diverse contexts, learners gradually internalize the patterns that no grammar book could fully capture.

FAQs

What is the difference between “is” and “are”?

“Is” and “are” are both present tense forms of “to be,” but they’re used with different subjects. “Is” pairs with singular subjects (he/she/it/singular noun), while “are” works with plural subjects (you/we/they/plural nouns). For example:

- “The cat is sleeping.” (singular)

- “The cats are sleeping.” (plural)

It gets tricky with collective nouns like “team” or “family,” which can take either form depending on whether you’re emphasizing the group as a unit or its individual members. In American English, collective nouns typically take “is,” while British English often prefers “are” for the same words.

How do you use “to be” in questions?

To form questions with “to be,” simply invert the subject and verb:

- Statement: “She is happy.”

- Question: “Is she happy?”

Unlike most other verbs, “to be” doesn’t need “do” or “does” to form questions. Compare:

- “She sings.” → “Does she sing?” (requires “does”)

- “She is singing.” → “Is she singing?” (direct inversion)

In negative questions, you can either place “not” after the subject (“Is she not ready?”) or contract it with the verb (“Isn’t she ready?”).

When should you use “being” versus “been”?

This distinction trips up many learners! “Being” is the present participle form, while “been” is the past participle:

- “Being” appears in continuous tenses: “He is being difficult.” (present continuous)

- “Been” appears in perfect tenses: “She has been here before.” (present perfect)

Think of “being” as expressing ongoing states or actions, while “been” indicates completed experiences or states that connect past to present.

Can “to be” be omitted in certain contexts?

Yes! English allows “to be” deletion in several contexts:

- Certain subordinate clauses: “The man [who is] standing there is my uncle.”

- Headlines: “[There are] Five injured in accident.”

- Some questions: “You [are] ready?”

- After “let”: “Let [there be] there be light.”

These omissions follow specific patterns and aren’t arbitrary. Learners should recognize them as conventional shortcuts rather than grammatical rules to apply freely.

What’s the difference between “was” and “were” in hypothetical situations?

In hypothetical or contrary-to-fact situations, traditional grammar prescribes “were” for all persons, even first and third person singular where “was” would normally appear:

- “If I were rich…” (not “If I was rich…”)

- “I wish he were here…” (not “I wish he was here…”)

This preserves one of the few remaining subjunctive forms in English. However, in casual speech, many native speakers use “was” in these contexts, and this usage is becoming increasingly accepted.

Conclusion

As we’ve journeyed through the multifaceted world of “to be,” we’ve seen how this seemingly simple verb carries remarkable complexity and significance. From its basic grammatical functions to its profound philosophical implications, “to be” truly stands as the cornerstone of English expression.

Whether you’re constructing simple statements, forming complex tenses, or pondering existential questions, understanding “to be” enriches both your language skills and your capacity for abstract thought. Its irregularities and challenges aren’t just grammatical quirks—they’re windows into the evolution of language itself and how humans conceptualize existence.

For learners, mastering “to be” marks a crucial milestone in English proficiency. For native speakers, appreciating its subtleties can enhance precision and expressiveness in communication. And for everyone, recognizing how this fundamental verb shapes our understanding of reality adds depth to our daily language use.

Remember, “to be” isn’t just about correct grammar—it’s about expressing the full range of human experience, from concrete observations to abstract philosophizing. As you continue to explore and use this versatile verb, you’ll discover that its possibilities, like existence itself, are virtually limitless.

After all, “to be” isn’t just what we do—it’s who we are.